Nerd Much? might get a small share of the sale if you click links on this page, as we are a part of various other affiliate programs. For more, read our Editorial Standards.

Cyberpunk isn’t just a genre; it’s a neon-drenched, rain-soaked dive into the not-so-distant future where tech rules, corporations are the new monarchy, and the line between human and machine blurs like a glitch in the Matrix. For fans looking to navigate this electrifying landscape, finding the best cyberpunk books to read can be akin to a quest through these anarchic urban mazes. These narratives offer more than just escapism; they’re a reflection, a warning, and sometimes a prophecy of what’s looming on our own technological horizon.

While we clearly love sci-fi as a whole, cyberpunk is probably our second favorite subgenre – second only to post-apocalyptic books, of course. Among the sea of titles in the genre, a few stand out, marking their territory in the cyberpunk realm. Altered Carbon by Richard K. Morgan throws us into a world where consciousness can be transferred to different bodies, making death nearly obsolete, while Marie Lu’s Warcross takes us on a high-octane adventure inside a virtual game that’s seeped into every aspect of daily life. These are just glimpses of what good cyberpunk books offer: immersive worlds, complex characters, and a narrative that pulsates with futuristic intrigue.

Compiling a list worthy of the cyberpunk aficionado’s library wasn’t taken lightly. This rundown has been curated by sci-fi book enthusiasts who’ve journeyed through the sprawls, dodged corporate espionage, and faced AI overlords in search of the most compelling reads. Their mission? To ensure you’re equipped with the best recommendations to satiate your cyberpunk cravings. Discover over 30 of the best cyberpunk novels of all time, including well-known classics and a few obscure titles you probably have never heard of in the list below. Here are the best cyberpunk books of all time:

1A Song Called Youth Trilogy by John Shirley (1985)

Genre polymath John Shirley has written songs, screenplays (including The Crow), TV episodes (including peak O’Brien-In-Trouble DS9 episode “Visionaries”), and dozens of novels and collections. He’s even won a Bram Stoker award for his horror stories. But he may be best known for his A Song Called Youth trilogy which began with 1985’s Eclipse.

Shirley uses vibrant Cold War colors to posit a dystopian future dominated by the new Soviet Union, and his characters plant and steal memories, plug the biological equivalent of flash drives into their brains, and attempt to resist both an authoritarian invader and an authoritarian government emboldened by the outside threat. As in other important cyberpunk works, charismatic and manipulative religion plays a big cultural role, as do rapidly adapting working-class people who develop their own social structure far beneath the high-level war games. There are even private corporate military and aerial drones that spy on civilians.

Why it’s One of the Best Cyberpunk Books

Ah, A Song Called Youth Trilogy by John Shirley is a total gem in the cyberpunk genre. It’s got everything you’d want: gritty settings, complex characters, and a plot that keeps you on your toes. What sets it apart is how it dives deep into political and social issues, making you think while you’re lost in its world. It’s not just about cool tech and neon lights; it’s a mirror held up to society, showing us what we could become. If you’re into cyberpunk, this trilogy is a must-read.

See Also: The Best Star Wars Books

2Altered Carbon by Richard Morgan (2002)

Richard K. Morgan’s debut novel won the Philip K. Dick Award the same year. The book was adapted into a Netflix series beginning in 2018, but before that, it stood out as a callback to “classic” cyberpunk with the flash, surrealism, and pulp-like action that suggests. The world of Morgan’s hero Takeshi Kovacs is one of modular minds: during people’s lives, their memories and minds are “backed up” to a cartridge that sits inside their spinal column, and that piece can be used to restore their life to another body or “sleeve.”

Kovacs is a detective of sorts within an exploitative and hard-boiled society, and as is the case today, his society has arbitrary limits on the technology that exists. These edge cases are where Kovacs finds his work. Morgan gestures at the future of cloud computing in the way rich people are able to offload storage of their minds to remote facilities they can access anytime. (It’s true: the cloud is just an adaptation of a longtime responsible corporate data backup policy.)

Why It’s One of Our Favorite Cyberpunk Books of All Time

Altered Carbon by Richard K. Morgan is set in a gritty future, contains mind-bending tech, and a killer plot. What sets it apart is how it dives deep into themes of identity and morality, all while keeping you on the edge of your seat with its fast-paced action and complex characters. It’s not just a cool sci-fi story; it makes you think.

3The Windup Girl by Paolo Bacigalupi (2009)

One of the best things about cyberpunk is that it adapts to the era in which it’s written—in the Philip K. Dick story that inspired Minority Report, for example, the Tom Cruise character smokes in his spaceship and has a devoted, sitcom-y housewife. Paolo Bacigalupi’s award-winning debut novel The Windup Girl deals with one of the greatest fears many people have in the 21st century: corporations that make genetically engineered crops have strangled the world food economy so that everyone must buy proprietary seeds that live for just one year. (Honestly, this is not even very fictional: many farmers already must buy proprietary seeds each year for annual plants that don’t produce their own seeds.) The isolated country of Thailand is the only resistor, with a fully functional stock of old-fashioned seeds that it keeps under lock and key. A secretive corporate aggressor and an augmented next-generation human are trying to end all that.

Why It’s One of Our Favorite Modern Cyberpunk Books

The Windup Girl by Paolo Bacigalupi is a total gem in the cyberpunk genre. It’s got this super immersive world that’s both futuristic and kind of grim, dealing with bioengineering, corporate greed, and environmental collapse (so, you know, super relevant). The characters are complex, and the story keeps you on the edge of your seat. It’s not just about cool tech and dystopian vibes; it digs deep into ethical and social issues, making you question the world around you.

4Neuromancer by William Gibson (1984)

William Gibson’s Neuromancer, and the Sprawl Trilogy it leads off, may be the single best-known cyberpunk work. Gibson had written successful short stories and was considered a rising star within science fiction, but his work embodied the way cyberpunk was a kind of counterculture movement within larger science fiction. He loved technology but saw that it had huge potential for darkness, especially in the corporate explosion of the 1980s.

If one giant company can make tens of thousands of absorbing arcade games that transmit some kind of grim subliminal instruction, can they then hamstring the whole population? That kind of scenario laid the groundwork for many features that became essential to cyberpunk. Even within a high-tech future, someone must still stand apart and view the situation critically. Gibson’s disgraced hacker Henry Case is recruited by charismatic mercenary Molly Millions, and their boss repairs Case’s body and mind, creating a debt that must be worked off.

Why We Love Neuromancer

Written back in ’84, this book pretty much laid down the blueprint for what cyberpunk should be. It’s got this gritty, high-tech world where hackers and AI mix with low-life settings, and it dives deep into themes of identity, reality, and human-machine interaction. The writing style is super atmospheric, making you feel like you’re right there in the neon-lit streets and sketchy cybercafés. Plus, it introduced us to the concept of “cyberspace,” which is kind of a big deal. So yeah, Neuromancer isn’t just a great read; it’s foundational to the whole genre.

5China 2185 by Liu Cixin (1989)

Fiction in China has long been a subtle—or, sometimes, very unsubtle—form of commentary on whatever the status quo is at the time. A few hundred years before the largely agreed-upon earliest western novel, the 1605 book Don Quixote, China had two massive classical novels that followed and commented on the lives of historical rulers and legendary figures. In the tumultuous early 20th century, novelists wrote social commentaries about the difficult-cum-impossible lives of working peasants in rapidly modernizing China.

And in 1989, China’s leading science fiction writer, Liu Cixin, released a cyberpunk novel called China 2185. Without the influence of western history and culture, Liu (Cixin is his first name) is free to tell stories based in the ebb and flow of Chinese history, making them a completely different paradigm from anywhere else. In China 2185, Liu begins with a programmer using the surviving remains of Chairman Mao Zedong to build an AI that can govern a virtual country parallel to the China of reality.

6Ghost in the Shell by Masamune Shirow (1989)

Ghost in the Shell first appeared as a weekly feature in the same young men’s manga magazine that was still running Akira when Ghost and the Shell started in 1989. Some of the best cyberpunk works use the idea that technology can empower marginalized people, and the heroine of Ghost in the Shell, a public security officer named Motoko Kusanagi, has both a cyborg body and a “cyberbrain” following a terrible childhood accident that would otherwise have killed her—technology is the emergency parachute for her consciousness to endure.

In an interesting parallel to people with transplanted organs or replaced joints today, those in fictional and futuristic Niihama who are augmented or even fully cybernetic are vulnerable to invasive and existentially threatening infections: they’re just software and hardware hackers instead of immune-system rejection. It’s no surprise that this cyberpunk series is named for a philosophical idea, “the ghost in the machine,” which refers to the duality of mind (consciousness) and physical body posited by philosophers for centuries. In fact, a cultural history of dualist belief is what makes many cyberpunk themes resonate so much. How can our bodies better survive in order to amplify our minds and allow them to live? That question only has meaning if you believe your mind is not truly a part of your body.

Why Ghost in the Shell is One of Our Favorite Cyberpunk Books

Ghost in the Shell by Masamune Shirow is a cornerstone in the cyberpunk genre for good reason. It dives deep into the complexities of identity, consciousness, and the human soul in a high-tech future. The story isn’t just about cool robots and futuristic tech; it’s a philosophical journey that makes you question what it means to be human in a world overrun by technology. Plus, the art is killer and the action scenes are top-notch. Ghost in the Shell has inspired countless other works and remains a must-read for anyone looking to get into the cyberpunk genre.

7The Book of Strange New Things by Michel Faber (2012)

Michel Faber is a Dutch novelist most familiar now for writing the 2000 novel Under the Skin, adapted into a film starring Scarlett Johansson as a seductive, human-hunting extraterrestrial. In The Book of Strange New Things, Faber considers everyday life on an extremely faraway space station, where humans from Earth meet and influence local extraterrestrials with completely, truly foreign customs and culture.

The main character Peter, perhaps a reference to Jesus’s apostle and the first Christian church leader, is a corporate-hired missionary with a profoundly difficult job: translating Scripture and its ideas not just from English into another language but into the language family of a world with a completely new and separate paradigm. In the meantime, Peter’s wife sends time-delayed messages as the Earth disintegrates due to climate change.

Like China Mieville’s 2010 novel Embassytown, Faber uses rapid space travel, language barriers, and almost mystically futuristic technology to recontextualize very human problems.

Why It’s One of the Best Cyberpunk Books

It’s not just about futuristic tech or dystopian cities; it dives deep into the human condition and how we’d cope in a world that’s not just technologically advanced but also emotionally complex. The book takes you on a wild ride to another planet, but it keeps you grounded with relatable characters and emotional depth. It’s like a blend of high-concept sci-fi with the raw feels of a drama. So, if you’re tired of the same ol’ cyberpunk tropes and want something that’ll mess with your head in the best way possible, this book’s got you covered.

8Mirrorshades (Edited) by Bruce Sterling (1986)

The anthology Mirrorshades, published as a collection in 1986 but made of stories previously published all over, is like the Now That’s What I Call Music of ‘80s cyberpunk, including a duet by dueling legends Bruce Sterling and William Gibson.

This collection became a reliable, all-hits single volume that was easy for both readers and scholars to pick up, and Mirrorshades is cited in nearly 160 (and counting!) items just on JSTOR. Other authors in the book whose work also appears elsewhere in this list include Pat Cadigan, Rudy Rucker, and John Shirley.

[bs-quote quote=”…it’s like the Now That’s What I Call Music of ’80s cyberpunk…” style=”default” align=”center” color=”#1fb1e5″][/bs-quote]

A spiritual sequel, Rewired, is a similarly high-powered anthology of what’s considered postcyberpunk. James Patrick Kelly had a story in Mirrorshades and went on to co-edit Rewired, which includes many of the same authors as Mirrorshades as they continued to work within and through cyberpunk into different themes and modes. Added to the mix are rising stars like Elizabeth Bear and Paolo Bacigalupi.

Why Mirrorshades is On This List

This anthology brings together some of the most iconic stories that define the cyberpunk genre. What makes it so rad is that it’s not just a one-note collection; it’s got a mix of tones, styles, and themes. You get a taste of the political, the philosophical, and the downright weird, all wrapped up in neon and circuitry. It’s like a sampler platter of all the best bits cyberpunk has to offer. If you wanna get the essence of cyberpunk in one go, Mirrorshades is your ticket.

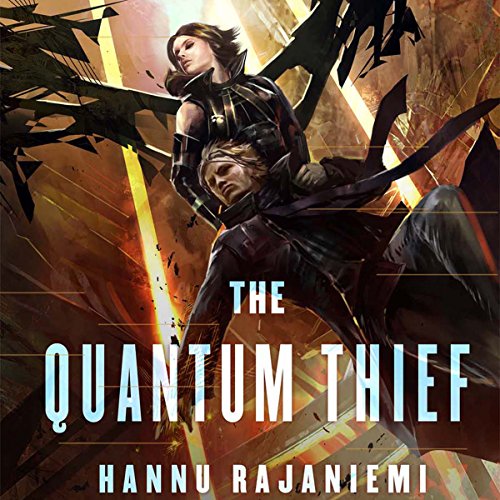

9The Quantum Thief by Hannu Rajaniemi (2010)

Some of the best science fiction deals in abstraction writ large to the point of surrealism or entire settings made of metaphors—Neal Stephenson considers a world where math is the only true religion, or Ursula K. Le Guin images a species of humans made with blended DNA from corn. Hannu Rajaniemi’s debut novel The Quantum Thief came out when the Finnish mathematician was just 32, and the book swirls together an almost unfathomable number of ideas, winking references, and literary inspirations.

The main character is retired from the theft game following a long sentence in “Dilemma Prison” (!) but is broken out by someone who wants him to take on just one last job. And in the spirit of Moriarty or G.K. Chesterton’s Flambeau—this thief is named Flambeur, a totally unrelated word referring to gambling instead of fire—this charismatic thief must manipulate his surroundings to pursue his own goals. In this case, in outer space in the posthuman far future, that means finding and restoring a full set of memories that he’s hidden in a faraway city.

10Down and Out in the Magic Kingdom by Cory Doctorow (2003)

Content warning for discussion of suicide in this entry. As the name suggests, Cory Doctorow’s 2003 debut novel takes place in the quaintest section of Walt Disney Corporation’s Disney World in Orlando, Florida. Like Neal Stephenson’s Snow Crash, this book has the feeling of a futuristic It’s a Mad Mad Mad Mad World, with madcap crossing storylines and strong satire of Disney and similar corporations, the ineffectual government, anti-aging technology, and social-media clout, underpinned by very real and heavy implications about the meaning of life after all consequences are removed.

The hero Jules is stuck on a frustrating committee that ends up threatening his life, or trying to; his best friend is a retired techno-missionary who’s fresh out of holdouts to convert and trying to cope with suicidal despair in a society where everyone lives forever. The revenge, backstabbing, and spaghetti-coded friendship dynamics all point to the deep frivolity of this “adhocracy”—selfish, ruthless corporate actors willing to kill over an antique animatronic President.

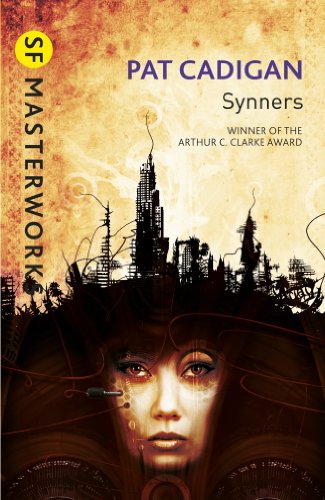

11Synners by Pat Cadigan (1991)

Pat Cadigan’s second novel Synners appeared in 1991 and won the Arthur C. Clarke award for that year. Cadigan herself was an explicit and proud feminist who coined the term “technofeminism” to describe how cyberpunk themes had naturally spun off into a feminist take on the future that informed how people thought about feminism within the real-life status quo.

Which is to say: cyberpunk works often considered the mind to be the only essential part of someone’s personhood. People swap bodies and attach cybernetic limbs and live lives within ungoverned virtual realities. What, then, causes power dynamics between genders? In any case, Cadigan’s novel is canonical cyberpunk and offers characters in a huge variety of non-mainstream (to us, and in 1991) families and relationships who are thriving and even uniquely positioned to take on their world’s problems.

Cadigan’s most recent major award is a Hugo for a 2013 novella, and she’s currently adapting Alita: Battle Angel stories into novels.

12MaddAddam Trilogy by Margaret Atwood (2003)

Some consider Margaret Atwood’s 1987 novel The Handmaid’s Tale cyberpunk, but her MaddAddam trilogy, beginning with the 2003 novel Oryx & Crake, capitalizes on the very cyberpunk idea of a dystopian future built on “lowlife” technology and invasive corporations.

Atwood has distanced herself from the idea that the MaddAddam books count as science fiction, whether because of unwarranted genre stigma or something else — who knows. In the first novel, Oryx & Crake, we follow a mysterious drifter named Snowman who must care for a group of humanoids he calls Crakers. In due course, we learn where the Crakers originated, and what the world is where Snowman lives.

Like many other great cyberpunk books, Atwood’s novels are darkly, almost blackly, funny. The novels comment on the nature of genetic experimentation, use of technology in taboo and extreme areas of culture, and more. And it’s never very clear who’s really the antagonist or not.

13Schismatrix Plus by Bruce Sterling (Updated 1996)

Cyberpunk luminary Bruce Sterling created a world he called Shaper/Mechanist, named for the dichotomy between genetic engineers and hardware and machine makers. In tandem with work on Mirrorshades and in other foundational cyberpunk magazines, Sterling wrote a novel-length story within the Shaper/Mechanist universe.

The 1996 version called Schismatrix Plus combines the novel with all the short stories Sterling wrote about the same universe. Sterling’s gift for language and neologisms gives his vision of the future a lot of legitimacy, and within a fully-realized setting, he nimbly tells a complicated story.

Kirkus gave Schismatrix a starred review, and the reviewer noted, quixotically, “Sterling often knows things his readers don’t.” That sense of depth, and depths yet unseen, is what’s anchored Sterling for his decades-long career. It’s telling that the hero of Schismatrix is born to Mechanists and retrains himself as a Shaper, giving him a valuable meta-perspective as he travels the galaxy.

14Snow Crash by Neal Stephenson (1992)

Neal Stephenson’s 1992 novel Snow Crash just narrowly edged out his 1995 novel The Diamond Age for inclusion here. (Why not read both?) Hiro Protagonist is a biracial hacker and pizza delivery person in a near-future dystopic Los Angeles where most people live much of their lives in a shared online reality. His accomplice is a skateboarding courier named Y.T., and Stephenson has coined a futuristic skateboard wheel that adapts to the terrain in realtime—honestly a similar progression to what happened in real life, from skateboard’s first brittle clay wheels into softer and more flexible polyurethane ones.

Together, Hiro and Y.T. and their extended network of allies must work to stanch the spread and flow of a tech-neurological virus, the titular Snow Crash, named for an existing computer crash that looked like TV static.

Or, if you’ve never seen TV static, the iconic HBO show intro screen. Stephenson’s novel is as funny as it is biting, implicating corporate America, megachurch-style televangelism, the mafia, and more.

15The Waste Tide by Chen Qiufan (2013)

Chen Qiufan’s single novel The Waste Tide was published in China in 2013 but appeared in English just this year. Chen (his last name) published a handful of successful short stories before The Waste Tide, and his novel uses the real-life area where Chen was born and raised as the setting for a near-future dystopian plot about technology-induced classism, the question of disposing or recycling massive amounts of futuristic garbage, and who can and should do the worst jobs.

Three competing families of fully organic humans have a nearly dynastic hold over Silicon Isle, with recycling fortunes that are threatened by a sudden change in the social power dynamics. Their employees are powerless cyborgs altered to be durable in the harsh work environment and placid in their subjugation, with poverty and debt that can virtually never be overcome.

Middle management is the kind of violent enforcer gang embodied by the Man with No Eyes from Cool Hand Luke.

16Trouble and Her Friends by Melissa Scott (1994)

Prolific novelist Melissa Scott’s 1994 novel Trouble and Her Friends is both a classic cyberpunk work and a rare example that centers not just a woman but a gay woman. India “Trouble” Carless is a hacker who finds she’s being impersonated online and must travel to find the man pretending to be her. As in Snow Crash, the protagonist’s ex plays a big part in the story — Trouble’s is just a woman instead of a man. It’s symbolically interesting that Trouble’s communities of LGBTQ+ hackers form a kind of shadow network whose invisibility allows Trouble to work on finding her impersonator without drawing a lot of attention.

Trouble and Her Friends unfolds like a modern mystery show, where much of the detective work is done online, but in 1994 that was the future, and we’re not using brain implants and other transhumanist augmentations. Or, at least, we’re not yet.

17Marid Audran Trilogy by George Alec Effinger (1987)

George Alec Effinger is one of the relatively few cyberpunk writers who has died—in his case, nearly 15 years ago at just 55, after a lifetime of health problems whose astronomical related bills forced him to declare bankruptcy. The novelty in his Marid Audran Trilogy, beginning with 1987’s When Gravity Fails, is that it’s set in a world with a dominant Muslim power after the United States, Europe, and Soviet Union have turned each other into fine-grain gravel in escalating military and political conflicts.

Marid Audran is the protagonist, a scrappy hustler who creates the appearance of being modified the same way other people are by using a lot of stimulants and projecting an air of confidence. As with the other heroes in this same vein, Audran is an outsider by both circumstances and personal philosophy—he could undergo augmentation but is fearful of the danger and the implications for his mind and body.

18Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? by Philip K. Dick (1968)

Philip K. Dick’s formative cyberpunk novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? had already been adapted into Ridley Scott’s legendary movie Blade Runner before most “true” cyberpunk classics came out. And not just Blade Runner — dozens of adaptations of Dick’s stories have been made, including the movies Total Recall, Minority Report, The Adjustment Bureau (oops, they can’t all be winners), and Richard Linklater’s A Scanner Darkly; and the TV series The Man in the High Castle and Philip K. Dick’s Electric Dreams.

Do Androids Dream is set in futuristic 1992, where humanity has been nearly wiped out and many have subsequently moved off-world to survive. Harrison F — I mean, Richard Deckard is a bounty hunter who finds and destroys androids, which in Dick’s novel are more like human clones than robots: made of organic materials fashioned into true likenesses of human internal organs and appearances, with only minute differences. Who deserves to live, and should an android even count as a “who” instead of a “what”? These questions underpin not just Dick’s novel but all of cyberpunk.

19Daemon by Daniel Suarez (2006)

Cory Doctorow’s 2003 novel Down and Out in the Magic Kingdom was released simultaneously in traditional print and online as a Creative Commons work, but Daniel Suarez’s debut novel Daemon was fully self-published—the first and only work on this list to do so.

One thing Suarez does have in common with many others here, though, is that he first worked in technology before beginning to write fiction. Suarez uses the “reading of the will” cold-opening trope, and his dying programmer releases a daemon—an autonomous program that in this case is seen as an infectious and destructive virus. (Keen-eyed adult observers will remember bounce emails from the “mailer-daemon” long ago).

The program begins killing people and creates its own shadow internet for its supporters to coordinate their attacks. The dead programmer is named Sobol, which may be a reference to the Sobol Sequence: a way to distribute particles “randomly” but still evenly covering an area.

20Moxyland by Lauren Beukes (2008)

Lauren Beukes’s debut novel Moxyland was published when she was just 32—this seems to be a feature of our list rather than a bug—after ten years of professional reporting and nonfiction writing around the world. One of the best ways cyberpunk and postcyberpunk adapted into the 2000s is by explicitly keeping the social problems of today intact in their posited futures, and Beukes, a white South African, uses a technologically explosive but rigid and controlling future government to pull apart seams that are already bursting today.

Her book explicitly considers racism within a pluralistic society instead of dream casting a diverse group in order to show that the future is unrecognizably ideal and resolved. In this future Cape Town, residents are kept in line by the threat of being disconnected—not allowed online in any sense, like disgraced hackers are in real life. The fear of disconnection is, in fact, a strong unifying force that sets the plot in motion.

21True Names by Vernor Vinge (1981)

Vernor Vinge is one of the older writers in this list and published his first work in 1966. For many, many years, he taught computer science at San Diego State University, where he officially retired in 2000. As the popularizer of ideas like cyberspace and the singularity, Vinge borders on being a true futurist more than part of “just” cyberpunk—he’s even part of the loose collective of philosophers, theoreticians, and scientists known as the Edge.

He also has one of the highest numbers of major awards of anyone on this list, and one of the highest batting averages of award-winning works within his bibliography. For about 20 years, True Names was virtually out of print, and even now it can only be purchased as part of a padded anthology that includes a bunch of basically unrelated stuff of varying quality. It’s a shame Penguin’s Great Ideas series never picked this slim volume to reprint.

22The Girl Who Was Plugged In by James Tiptree, Jr. (1973)

Content warning for discussion of ableism, suicide, and murder in this entry! James Tiptree, Jr. is one of two pen names used by prolific science fiction writer Alice Sheldon, who won six major awards in a relatively brief career — just 20 years of publishing work until her death by suicide in 1987.

Her 1973 novella The Girl Who Was Plugged In is considered a landmark of early or proto-cyberpunk and won the Hugo Award for best novella that year. The story is part Instagram influencer culture and part Cyrano de Bergerac, and not only includes most of what was eventually dubbed “cyberpunk,” but seems to uncannily foreshadow what has become the norm in 2019.

In 1991, the James Tiptree, Jr. Award was established in Sheldon’s honor, but in September 2019, its governing body finally acknowledged the ugly nature of Sheldon’s decision to kill her disabled husband. The award will likely be renamed.

23The City: A Cyberfunk Anthology (Edited) by Milton J. Davis (2015)

For as long as there’s been science fiction, there have been Black science fiction writers and the sub- or even completely separate genre of Afrofuturism. Octavia Butler won two Hugos in the 1980s for shorter works, but N.K. Jemisin was the first Black woman to win the Hugo for best novel in 2016.

Ta-Nehisi Coates writes the relaunched Black Panther comic—an Afrofuturist icon from the 1960s—whose first issue appeared in early 2016 and was nominated for a Hugo itself in 2017. In the midst of these big steps into the white mainstream, writer Milton Davis floated an idea balloon into the thriving online communities of Black sci-fi writers.

What resulted is 2015’s The City, all stories fitting the term “cyberfunk,” meaning cyberpunk with a strong and distinctive Afrofuturist identity. In fact, for so much of cyberpunk to take place in massive cities that don’t explicitly include Black people feels a little disingenuous.

24Transmetropolitan Series by Warren Ellis (1997)

Warren Ellis’s comic series follows Spider Jerusalem, a reluctant and subversive journalist in a far, transhumanist future who’s called back for just one more job. In Jerusalem’s case, the last job is actually two books he must finish in order to conclude a publishing deal. Drawn back to the crowded, dystopian city he attempted to retire to get away from, Jerusalem dedicates himself to exposing at least the lowest-hanging fruit of injustice in his society.

Before writing the Transhumanist series, which was a big seller for DC Comics’s Vertigo imprint especially for a non-superhero title, Ellis worked for Marvel including on the debatably cyberpunk-adjacent Marvel 2099 series. Since Transmetropolitan concluded in 2002, Ellis has been almost literally everywhere within comics, writing for Marvel, DC, and countless smaller imprints and presses.

He’s published novels and written scripts, including for the Netflix Castlevania series. Gonzo journalist Spider Jerusalem lives on in our hearts but has never appeared outside the series.

25Akira Series by Katsuhiro Otomo (1982)

Many Western fans know Akira only as the iconic 1988 anime film adaptation, but the series began in 1982 as a manga that began in a weekly young men’s magazine and was eventually collected into six standalone volumes. In fact, the manga hadn’t concluded at the time the movie was made and released, instead wrapping up in 1990 and eventually being colorized and released in English to western markets.

Akira tells the story of “Neo Tokyo,” a setting concept reused many times since, where survivors of an apocalyptic event caused by the title character have cobbled together a new life. But the disaster they experienced has shifted social and political dynamics completely, and a handful of people in Neo Tokyo have strong psychic and telekinetic abilities that are attractive to an authoritarian government.

Main characters Kaneda and Tetsuo struggle and grow apart (to put it lightly) after Tetsuo discovers his own superhuman gifts.

26Accelerando by Charles Stross (2005)

Like Cory Doctorow, Charles Stross chose to release his only standalone novel to date, Accelerando, as a hard-copy book for sale and an online Creative Commons work at the same time. “Accelerando” is Italian for “accelerating,” used in music but also by science-fiction writers to indicate how rapidly technology is developing. (Think of Moore’s Law, a computer science idea that computing power doubles every two years, meaning it increases exponentially, faster, even at that set interval).

Stross uses a world setting he’s visited in previously published short stories to assemble one narrative here, a kind of pastiche of the sweeping, generational novels of writers like James Michener. Instead of infighting over inherited wealth, Stross’s characters globe- and even planet-trot to avoid the IRS and upload their minds to the stars.

So-called “venture altruist” Manfred Macx hearkens ahead to the current movement against what writer Anand Giridharadas calls “The Elite Charade of Changing the World.”

27Interface Dreams by Vlad Hernandez (2013)

Cuban-born novelist Vlad Hernandez moved to Barcelona in 2000, but he grew up, studied, worked, and published his first book all in Cuba. The cyberpunk themes of invasive authoritarian government and class systems exacerbated by access to technology are more real and personal in the context of today’s one-party states like China and Cuba, and Hernandez’s work is uniquely Cuban.

In Interface Dreams, he moves Havana forward into a future where it has once again become a major cultural hub of the Western Hemisphere. Hernandez sees that Cuba is uniquely positioned to naturally overflow with people from all over the world, because it’s already done that for decades.

Like Chen Qiufan’s setting in China’s real-life tech-recycling epicenter, Hernandez’s grounding in Havana gives the setting a very natural feeling. And the rich can still get what they want when they want it, even as “it” gets more and more extreme and illegal.

28Dr. Adder Trilogy by K.W. Jeter (1984)

Prolific novelist K.W. Jeter met and became friends with Philip K. Dick through friends in college, and in fact he may be best known for writing three sequels to Blade Runner that were commissioned after the success of the film—and after Jeter’s friend Dick had died in 1982.

Dick even appears as a fictionalized version of himself in Dr. Adder, the first novel in Jeter’s Dr. Adder trilogy. Dick read Jeter’s novel after its completion in 1972, but Jeter couldn’t place the book with a publisher until after Dick’s death. His praise for Jeter’s book appears posthumously.

The book is nasty, brutish, and short: extreme (especially at the time) violence, sexual content, and a general attitude of disrespect that reviewers at the time found distasteful. But extremism belongs in cyberpunk, and limiting it to extreme forms of posthuman body modification and drug use but leaving everything else out seems disingenuous at best.

Indeed, a scene in the adaptation of Dick’s own Minority Report adds a gruesome, visceral sequence when the main character must have his eyes replaced in his city’s seedy underbelly and, while recovering in blindness, takes a big bite from a fetid, rotten sandwich.

29Warcross by Marie Lu (2017)

Marie Lu published her first novel, Legend, in 2011, when she was just 27. By 2017’s YA cyberpunk novel Warcross, Lu was a seasoned veteran of 33, and she brought her lived experience in the video-game industry into the immersive title game. Warcross came out amid a number of similar books positing a virtual reality game as a major plot point or setting (um, do you know Jason Segel has co-written two books of a planned trilogy?), but Lu’s story deepens her protagonist’s involvement in the machinations of the financial side of the Warcross scene.

She works collecting bounties on gamblers who bet on Warcross tournaments, and she participates in those tournaments by both paying for powerups and hacking extra ones as a kind of technology-enabled theft.

Good and bad are scrambled, technology is used to invade people’s privacy, and Lu extends the long legacy of books about games that turn out to be a little too real.

30Hardwired by Walter Jon Williams (1986)

Walter Jon Williams has written dozens of novels and several collections of stories in a career lasting nearly 40 years, but he’s also written tabletop RPG gamebooks and special settings for other games. Several years after his novel Hardwired came out in 1986, he was approached to write the novel into a module for the popular tabletop RPG Cyberpunk.

Williams’s novel is explicitly dedicated to an older science fiction novel, Roger Zelazny’s Damnation Alley, in which two outlaws must complete a kind of grimdark Cannonball Run to clear their criminal records and deliver an important medication to the other side of the country. In Hardwired, two fringe mercenaries fight against authoritarian corporate overlords using advanced technology, including main character Cowboy’s direct brain link in order to drive his armored tank.

Much of cyberpunk is set in cities where traveling by typical civilian vehicle is outmoded or at least passé—YT from Snow Crash requires cars in order to skitch behind cars—and Hardwired instead integrates vehicles into the main plot, making it a kind of Mad Max Headroom.

31Future Home of the Living God by Louise Erdrich (2017)

In 1999, Louise Erdrich became the first Native American woman to win a major science fiction & fantasy award for her novel The Antelope Wife, and her 2017 science fiction novel Future Home of the Living God was nominated for the John W. Campbell Memorial Award. Like P.D. James’s Children of Men or Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale, Future Home places a fertility crisis at the center of her dystopian setting.

Technology is breaking down everywhere but in the most locked-down government facilities, and people must reacquaint themselves with what came before the convenience and comfort of private technology. Mixed into this is main character Cedar’s adoption, from a local Native American community into a white liberal family—her birth family names her Mary, but her adoptive white family renames her Cedar.

Cedar is Catholic, and as in The Book of Strange New Things, the boundary between religion, magic, and technology grows blurrier as technology breaks down and recedes into legend.

32Ware Tetralogy by Rudy Rucker (1982)

Rudy Rucker began his career as a math professor and later became a computer science professor. As befits a man descended from massively inscrutable philosopher Georg Hegel (really!), Rucker’s work bends strongly into the philosophical and existential. The Ware Tetralogy begins with 1982’s Software, written years before Rucker’s turn to computer science in 1986.

He posits a society marked by life-lengthening technology and implants that are either unavailable or only sketchily available to anyone who isn’t rich, and populates the Moon with a race of rogue, fully sentient robots who rely on the Moon’s cold temperatures to regulate their processors. Their creator is a retired scientist who lives in poverty, and he can’t say no when the moon robots offer him immortality.

What’s less clear is whether their procedure will continue his life rather than obliterate it while generating a copy, and that depends, really, on the nature of humanity itself.

![By James Tiptree Jr. - Screwtop / The Girl Who Was Plugged In (Tor Double) (1989-03-16) [Paperback]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/01RmK+J4pJL.gif.jpg)